Background to Nigerian Oil

Oil was discovered in Nigeria as far back as 1938, but the reserves were not exploited until 1958 because the Second World War constrained the oil majors – Shell and BP at the time. Thereafter many multinationals were attracted to the sector and these included Chevron, Elf Oil, Total Oil, etc.

Oil has since 1970s provided the corrupt elite huge resources and dominated the economy as the national oil company joined Oil Producing Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1973 when the price of oil rose to $8 per barrel. Oil revenues constituted 95 percent and 80 percent of the country’s foreign exchange earnings and government’s expenditures for greater parts of the last four decades.

The huge resources realised from this source were squandered by the ruling elite on frivolous projects. Only lip service was paid to diversification of the economy, even when the constitution of the country expressly made this clear as the way to go. But instead, a greater percentage of resources ended up in the pockets of successive politicians and military administrators as a result of corruption; while agriculture, the hitherto mainstay of the economy was abandoned.

This so called Dutch disease was not unusual with oil and mineral producing countries that suddenly found themselves overnight as a rich country. But not a few of such countries have learned the necessary lessons from the events of the past to take precautions on how to organise the oil business in the best way possible to safeguard their interest. And this was the reason that some had taken the path of nationalisation by the state controlling the oil business in owning the technology and know-how, marketing and administration. This has been a progressive step, however limited this might be in not meeting the requirements of workers control and management of the sector and the economy at large.

Nigeria is an exception to this rule as its leaders exhibited the true characteristics of a typical comprador bourgeoisie. They prefer the role of an agent and remain at the level of partnership. Their involvement has been limited to joint venture arrangements with the oil majors who took advantage of the relationship; as Nigeria became a rentier capitalist state. Even infrastructures that are critical to business and inevitable for improved standards of living like electricity, water, communication, transportation, etc could not be provided efficiently.

Since the 1980s, Nigerians have been critical of the operation of the oil business which has been organised to the disadvantage of the common people. And they have raged over this when it concerned the unilateral increase of the pump price of oil to the consumers. This has caused mass protests by the working people in the last two decades, especially in 1988, 1993, 2000, 2003, 2006, 2007 and 2012.

International Politics and Oil

The importance of oil, since it was discovered in the USA in the late 19th century, corresponded with the era of industrialisation that required oil as the lubricant in driving industry – machines, lighting for malls or shops, domestic purposes, and to power railway, air and auto transportation systems. Its role in industry and commerce contributed in no small measure to the growing World economy.

The uneven geographical distribution of oil across the globe explains why the oil producing countries wanted to be in full control of the product. On the other hand, the developed countries, that are the major oil consumers, wanted to wrestle control from them. This was the case for agricultural products – cash crops that served as raw materials for the industries in Europe from the poor nations under the control of the hitherto colonial dictatorships.

OPEC functioned to rebuff such control over oil prices by the developed countries. Member countries of OPEC were able to assert their independence as a collective. Economic wars had been waged over the oil price until OPEC was successful in achieving a higher price for the produce by its members in the early 1970s. However, this helped to precipitate the economic recession of the 1970s after the long global economic boom from the Second World War.

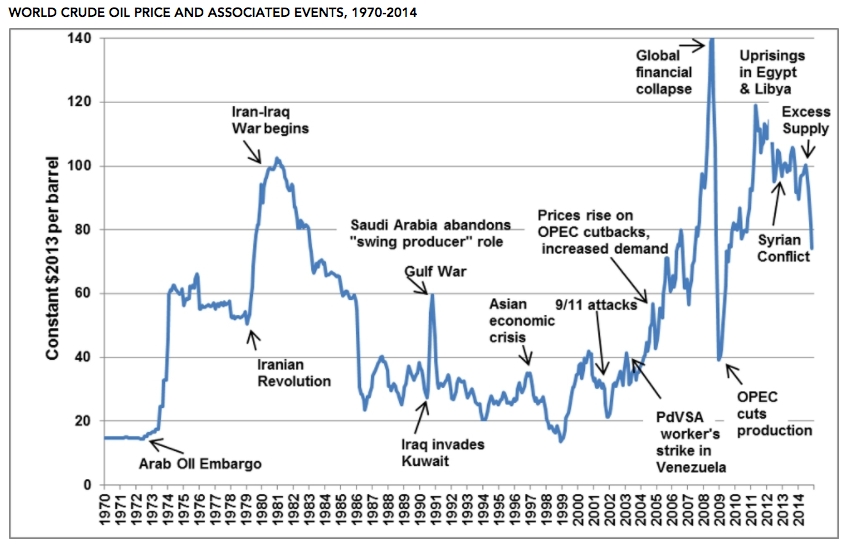

energy.gov/eere/vehicles/fact-859-february-9-2015-excess-supply-most-recent-event-affect-crude-oil-prices

Evolution of the Present Crisis of Oil Price War

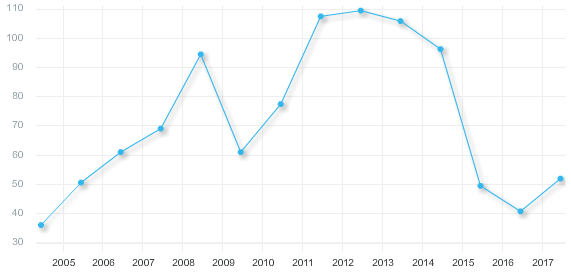

Before the world financial crisis of 2009 that emanated from the US, the price of oil stood at $144 per barrel. This dropped to $34 per barrel when the crisis reached its peak. But with the enormous economic growth and activities going on in China in such areas as infrastructural development, communication, transportation, construction of roads, bridges, housing, etc. the situation rubbed positively on the entire world economy including the oil and gas sector. For this reason, the price rose to $77 per barrel and $100 per barrel in 2010 and 2011 respectively. The slow down in China’s economy in 2014 and thereafter caused this to drop to $84 per barrel in June – October and further dropped to $55 per barrel by the end of 2014. The graph below shows recent changes in the price of oil which is currently just over $50 a barrel.

Sometimes war or crisis in any of the oil producing countries could lead to fluctuation in the price attached to oil in the world market. This was the case in the gulf war between Iraq and Kuwait[1] in the late 1980s. Such insecurity may be currently arising with the hostilities between Saudi Arabia (and other gulf states) and Qatar and as a result of Saudi invasions of Yemen.

China and India were the two countries that started buying more of Nigeria’s oil when demand from the US tailed off. The US had been the largest imported of Nigerian crude oil, but did not take a single barrel over the last five years.

OPEC Basket Price ($ per barrel)

Two reasons could be adduced for why buyers from USA are not forthcoming like before. First was that the quantum of their demand that has reduced since the 2008 world financial crisis. The policy directive of the US standardised fuel efficiency for automobiles after the bailout intervention of the automobile companies by US government in 2009 is another possible factor in the reduction in demand; as new vehicles now consume less fuel. This is also not unconnected with the state of economic growth in the US. This now stands at around 2 percent, half the rate in the 1990s. Second was the new technology of converting solid Shale Oil and Tar Sand to liquid crude oil. The two reasons therefore added to the present crisis in limiting demand for oil on the one hand and increasing supply of oil from unconventional sources on the other.

This was the US where the total domestic crude oil production dropped from 7.5million to 5.5million barrels per day from January 1990 to January 2010 respectively. But due to the new technology of converting Shale Oil to liquid in such fields as North Dakota and Texas, US companies were able to increase her crude oil production from 5.6million barrels per day from June 2011 to 8.7million barrels per day by June 2014. This increased later in 2015 to 9.6million barrels. In three years, domestic oil production in the US increased by 3million barrels per day, a 55 percent increase.

These developments brought US production next to Saudi Arabia as the highest global producer of oil. US possesses the capacity of being the number one producer of oil in the coming period as companies from there have the potential of producing 3 trillion barrels of oil from this latest source in comparison with production coming from the entire oil producing countries put together that could only produce 1.5 trillion. But the constraint militating against doing so in the short term is the problem of the lack of technology to produce Shale Oil efficiently. The present cost of converting US Shale Oil stands at $36 per barrel, while Saudi Arabia is able to produce at a cost of only $10 per barrel. Canada’s Tar Sand are being produced at a cost of $41 per barrel; Brazil oil at $45 and Britain at $52. Other deep offshore oil in the Gulf of West Africa including Nigeria also has the same problem of producing at a relatively high cost.

In addition to the present oil price reduction due to the limited demand for oil in the case of China, USA and Europe, the other reason for the crisis is the supply side where production of oil to the market is beyond proportion. In this case, it was not only the US that increased oil production during the period under consideration. Canada followed the same path by converting Tar Sand (solid) to liquid crude oil. By this she was able to increase her production from 3.2million to 4.3million barrels per day in 2008 and 2014 respectively. Iraq increased hers by about a million barrels per day. Saudi Arabia OPEC quota increased to 10.3milllion barrels per day as at May 2014. Iran that was sanctioned earlier also increased her production to an estimated one million barrels per day.

The various key players in the global oil business had reason for their role in the present oil price fluctuation. Industrialists in US and Canada for instance along with their allies in other developed countries have ever been looking forward to cheap oil to power their industries and other commercial activities. But the skyrocketed leap in the production by US and Canada at high cost was never envisaged. Therefore rather than championing the cause of lower prices for oil, as it did in the past, the US government is contrarily supporting an increase in the price of oil at least to the level that her investors would be able to make profits rather than loss from Oil Shale and Tar Sands. While US investors in the new technology are expected to make profits only if the price of oil is stable at $50 per barrel. In contrast, Saudi Arabia can make ends meet at $30 per barrel.

Saudi Arabia increased her production after the global financial crisis, at least until late 2016. It was believed that this was to try and undermine the US production of expensive oil from shale and oil sands. Another reason for this action is associated with the politics of the region over Syria and Syria’s supporters such as Russia and Iran. None of the two reasons could be discounted as Saudi Arabia holds strong views on both politics and oil. The later is seen as a weapon of politics that could be used to get support for her political views.

The Crisis in Perspective

All players were affected by the drop in the price of crude oil from $144 in 2008 to only $30 in January 2016. This price fall also affected the world economy and was affected, as this has yet to fully recover.

In the usual way of the bourgeoisie in the period of crisis, steps were taken to conserve funds in order to ensure profitability by cancelling or postponing investments in new production ventures. Jobs were also cut to achieve the same purpose. These cutbacks included Canada’s Athabarcatar Sand and deep waters (offshore) of the West Coast Africa. Combined, they shelved $200 billion worth of spending on new projects. Shell postponed the South West of Nigeria project of $12 billion development in the Atlantic Ocean; the French firm Total postponed its final investment decision on Zinia on the coast of Angola. In all, projects worth $380 billion were put on hold, while other spending on fixed assets in the oil industry were halved. Exxon and Chevron, two of America topmost oil producing companies were reported to have seen their earnings drop by 52 percent while income for the later fell by 90 percent from the earlier position in 2014. Halliburton laid off 7 percent of its workforce numbering 6,000 while other firms announced equivalent reductions as a result of which hundreds of thousands of workers lost their jobs. In the US alone, 86,000 jobs were affected. In Britain, 20 percent of oil workers were affected in some of the oil firms while those that were able to retain their jobs did so at the expense of a 10 percent pay cut.

The effect of the crisis snowballing to other sectors was restricted to some banks that finance oil business, especially in USA. But this was marginal and could not affect the world economy as a whole. The industrial world that is the major consumer of oil benefitted from the drop in oil price and this was also the case with the other non-oil producing countries, while the economies of oil producing countries suffered from it. The slowdown in the aggregate demand of oil producing countries thereby affected the world economy negatively.

The Financial Times reported how the balance sheets of three big US banks were dragged down as they related to the cost of bad energy loans. Another Bank, Citigroup, reported a 32 percent rise in non-performing corporate loans. Some of the Nigerian banks were affected and this is understandable as not a few of them deal with domestic oil merchants.

The Saudi government was able to manoeuvre as its aim in the short term was to drive some of the producers out of market. Saudi Arabia apart from being the largest global producer of oil, has $750 billion in cash as foreign reserves upon which she is realising over $3 billion annually. Nevertheless, the effect of the crisis impacted on the Saudi Arabian economy. The government cut its budget and looked for other sources of government revenue. In doing this, the government decided to sell some assets, including airports, and a country noted for not charging income tax on citizens, contemplated charging value added tax (VAT) and increased prices of electricity and water.

Russia was also affected. With Western sanctions, especially for oil, over the war in the Ukraine, this new crisis further heightened the economic challenges. For this reason, the value of the Russian rouble in relation to the US dollar declined by 50 percent, an indication of the crisis facing the Russia economy.

In the case of Nigeria lately, the crisis has led to a mild recession. The economy declined by an estimated 1.5% in 2016 after growing by as much as 6.5% over the last three years. However, the effect on the working class has been much more serious. The cost of living has increased significantly, making life generally difficult. In addition, in many of the states and local governments workers are owed arrears of salaries of at least six to nine months.

Not a few people subscribe to the argument that both external as well as internal factors are responsible for the recession. Prominently associated with the former is the issue of low price of oil and drastic reduction in the demand for Nigerian oil. While internal factors hinge on primitive accumulation (or corruption) by public officers and the neoliberal policies (privatisation commercialisation, liberalisation and devaluation) used by the government to serve the interests of the rich while making the poor poorer. The Boko Haram insurgency and the militant groups that resurfaced in Niger Delta significantly contributed to the problem. The government committed huge resources to fight the war against Boko Haram while production of oil dropped drastically from 2.2million barrels to 1.7million barrels as a result of the activities of the Niger Delta militant groups.

The resultant effect of the crisis on the economy has been grievous. This is the reason the 2016 budgets had to rely on foreign loans to finance about 50 percent of the budget. Funds from oil will only provide for a paltry N800 billion out of the budget of over N6trillion. There is an improvement in the budget of 2017 in this regard as 40 percent of its finance is to come from oil, amounting to nearly two trillion of the total budget of an estimated seven trillion. Though there is nothing bad if loans are utilised successfully in achieving the purpose of development and providing for the welfare needs of the working people. But if the past is anything to go by, a greater percentage of such loans are likely to end up in meeting current expenditures and by implication ending up in the purse of individuals, public functionaries and their business partners in the form of corruption.

A greater percentage of the country’s GDP is now sourced outside oil, so oil’s contribution to the overall GDP is now only about a quarter. But oil still contributes about 95 percent of foreign exchange and 85 percent of government’s income. The important position of oil is responsible for the downturn presently experienced in the economy.

The fall in the price of oil brought about a decline in the revenue of governments at all levels since early 2016. The total revenue available for the governments of the three tiers in the first month of 2017 was N370 billion.[2] This can be compared with 2009 when the available revenue was, for instance, put at about N323 billion and N317 billion for March and April 2009 respectively. But the argument for such dwindling of revenue could not compensate for why the governments have abandoned their responsibilities to the working people. It was for this reason (gap in revenue generation) that loans were procured.

The situation of the economy shows how gloomy the future is going to be and this calls for urgent and drastic policy that could alleviate the problem. One of the challenges confronting the present government therefore is how to grow and diversify the economy especially in agriculture, manufacturing industry and solid minerals. Other areas that call for attention include the unemployment rate presently that is put in the range of 24 percent, bank lending rate that is 30 percent and the inflation that is presently estimated at over 12 percent.

The foreign exchange rate that was formerly a dollar to N157 and N170, at the official and parallel levels in 2011. This jumped to about N400 and N500 respectively in 2016. This continued up to the first quarter of 2017 when the intervention of the government stabilised it at around N300 to the US dollar.

It is not fortuitous that the Buhari led government could not deliver on its promised welfarist programme. Not a few have been disappointed by the inability of the government to deliver on its election promises. The president was on record in promising the people allowances for the teeming unemployed people, free food for the school children, resuscitation of the textile industry, provision of social infrastructures, reversing the past policy of wholesale privatisation in the electricity and energy sector, and that of the privatisation policy in general. The government instead of pursuing such promises that coincide with the demands of the common people, limited the whole business of government to the fight against corruption and the Boko Haram insurgency.

Events of the past have shown clearly that hardly anything could be achieved to grow the economy and bring about development without fixing such key sectors as education, electricity and banking/finance. For this reason, it would be erroneous to talk about providing electricity that could be enough to power industry and households when the government’s plan is limited to just 10,000 megawatts over four years. In reality, the country is estimated to need nothing less than 100,000 megawatts – much of this could be provided if the oil companies were forced to end gas flaring and provide fuel for the power stations.

Also anything short of the government taking full control of the entire banking/finance sector for its strategic role in shaping the economy and turning it around would not be likely to lead anywhere. This is why the government is reduced to criticising the banks for imposing high interest rates and is itself helpless in correcting the situation. The policy of the government in respect of agriculture and industrialisation would amount to naught if such a state of helplessness in the face of the high cost of finance is allowed to persist.

Conclusion

The above analysis leads us to the conclusion that the benefits of the oil business have been limited to the rich class. That is the oil merchants, multinationals, public officers (politicians) and bureaucracy in the oil producing countries. This has been at the expense of the working people, despite their important role in the exploration and production of oil.

Now that the oil business is going to be taken over by players in the developed countries, this will in no little way affect the economies of the OPEC members in the coming period and likely going to lead to depression in such countries. This may be like the 1960s, with many African agricultural commodity producers recording falls in the price of their produce. The likelihood of such a scenario is to heighten poverty in the oil producing countries that hitherto enjoyed relative economic stability in comparison with other less developed (non-oil producing) countries.

In the event of the crippling economies of these countries, political and industrial tension from the working people in the direction of the ruling class is a possibility of what is to going to happen in the coming period. The end result will be determined by the balance of forces between the capitalists on the one hand and the working people on the other hand.

Capitalism has no future in meeting the needs of the working people as it is constrained by the primitive accumulation syndrome for the best interest of its class. The oil sector could not be exempted from this general rule. For this reason, a way out of the vicious circle of poverty would be to get out of capitalism by way of nationalising the oil economy that would need to be put under the democratic control and management of the working class from below. This would provide the surest way to create enough wealth to be appropriated equitably in favour of those that work. Thus allowing their welfare, intellectual and reproduction needs to be met and guaranteeing the working people a better place in the changing world.

by Biodun Olumasu

[1] They are both oil producing countries in the gulf region.

[2] This is the figure is for January 2017 revenue allocation for three tiers of government