Africa was the last region of the world to be sucked into the pandemic and thus far appears to be the least affected. By mid-April the total number of recorded Covid-19 cases in sub Saharan Africa was over 10,000, with more than 500 deaths. Only Lesotho, a small landlocked country surrounded by South Africa, had no recorded cases. A significant number of the confirmed cases to that point were among the rich and privileged, including government officials, captains of industry and family members, pro-government online personalities and such like. This is a false picture of the disease spread, the seemingly low level of infection, compared to other regions, due to grossly inadequate levels of testing.

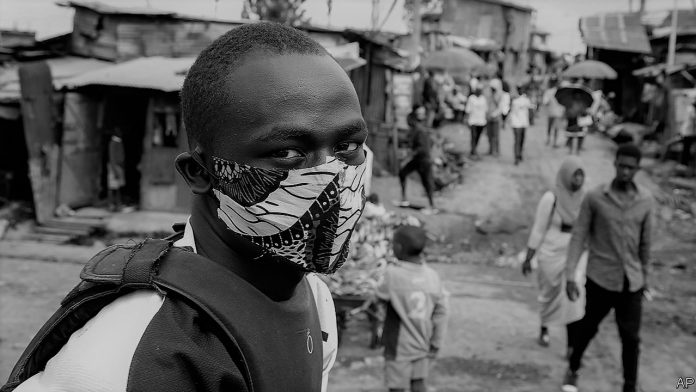

Bosses and politicians have privileged access to getting tested whilst Africa’s vast working-class people have virtually none. Bosses also have the luxury of being able to self-isolate in their mansions whilst for the millions living in shacks, slums and overcrowded apartments, self-isolation is an impossibility. The virus has once again shone a light on the millions of people who barely eke a living during ‘ordinary’ times, let alone during times of such ecological, health and increasingly now economic crisis. With vast swathes of the African population in informal and intensely precarious employment the so-called ‘hunger virus’ is as much a threat as the new coronavirus. UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, put the situation in perspective, noting that “Africa is in urgent need of test kits, masks, ventilators, protective suits for health workers…without a massive mobilisation we will have millions and millions of people contaminated, which means millions of deaths”.

But what he and the rest of his class will not say is why and how Africa arrived at a situation today of wide-scale shortage of all manner of essential resources – housing, dietary, healthcare and others – with wide-spread and deep levels of poverty, creating a working class population with such potential vulnerability to this pandemic. It is clear that the pandemic represents such a threat to life in the immediate short-term because over the longer term the combined under-development of the social determinants of health across the continent has grossly enfeebled ever-growing and increasingly vulnerable sections of the population.

Africa is a very rich continent with exceedingly poor people. At the centre of this is a long process of relentless capitalist exploitation of its resources by imperialist forces, aided by a handful of local bosses and state officials, which has seen the wealth derived from this richly endowed continent flowing out into the offshore accounts and banks of global capital. The threat of coronavirus results from global capital’s ruthless exploitation of the Africa continent and its people in search of profit.

The unhealthy backdrop of colonialism and neoliberalism

Gordon Brown once said: “the days of Britain having to apologize for its colonial history are over”. But that past, which actually extends even further to the capture of over 12 million men and women enslaved to work in the Americas through the 18th and 19th centuries, was, as Karl Marx described it, one of “the chief moments of primitive accumulation” laying the foundations of modern capitalism.

An important aspect of colonialism often overlooked is how, post-WWII, this long colonial exploitation deprived countries in Africa of the fiscal space countries in most other regions had to implement the Keynesian welfarist policies which helped sustain economic growth and develop systems of health and welfare underpinning the improvements of health and life expectancies through to the late 1970s.

In Europe, Latin America and Asia, independent countries governments could latch onto the sails of expansionary fiscal measures to establish or bolster industrial bases and institute social services from the late 1940s. But across Africa, colonial governments continued to squeeze every millilitre of juice they could from their African possessions. For example, in the UK it goes without saying that such extractions from the continent contributed to funding the establishment of, amongst other things, the NHS. It wasn’t until two decades later, during the 1960s, that the so-called “winds of change” blew to Africa. Shortly after, the “thirty glorious years” of post-war capitalism came to an abrupt end, but there was still cause for optimism as the Union Jack and Tricolour were torn down and replaced by a plethora of African national flags.

New, native rulers took steps to build their material base and legitimacy. Interventionist states, often via national development plans and some form of ideological “allegiance to socialism”, put in place massive public works programmes. In the first decade and a half of independence schools were built across the continent, leading to an over 70% increase in primary school enrolment. Higher institutions were established producing more graduates in a generation than the total of African graduates trained at home or overseas during the entire colonial period.

Healthcare delivery was given particular attention, with most countries committed to programmes aimed at providing public health for all. Public hospitals were built in cities and health centres in rural areas, resulting in significant improvements in the quality of life, even though Africa still lagged behind the rest of the world. In 1960, there was an average of 1 doctor to 50,000 people, compared to 1 to 12,000 in other low-income countries. By 1979 this had risen to 2 doctors per 50,000 people. Average life expectancy was 39 years in 1969, against 42 years in other developing countries. By 1979 this had risen to 42 years. Child mortality (for children between 1 and 4 years) fell from 39 per thousand children (as against 23 per thousand in other developing countries) to 25 per thousand children in the same period. Though relatively small, these improvements were immensely significant, signifying a trend of improvement and growth.

By the mid-1970s, the illusion that capitalism had conquered its boom and bust tendency was blown to smithereens by the intense and long-term economic crisis of the period. As the weaker trees are more easily blown away from the roots by a windstorm, African countries were hardest hit. Whilst GDP per capital for all developing countries fell from 3.5 for the 1960-70 period to 3.2 for the 1970-79 period, that for Africa fell from 1.4 to 0.2. Africa’s share of exports by non-oil exporting developing countries shrunk from 15% to 11% in the same period.

This ended the strategy of import substitution across the continent, an attempt to copy economic strategies pursued earlier in Latin America and Asia and paved the way for the 1980s “lost decade”. The template for this was laid in 1981 with Elliot Berg’s report published by the World Bank, ‘Accelerated Development in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Plan for Action’. The report was supposed to help African countries put the slowdown in their development in the 1970s in proper perspective. Not surprisingly, it didn’t identify global capitalism as the central problem. The document argues that there was too much government, and that this was getting in the way of private capital providing solutions. As across the rest of the globe, market-driven liberalisation was presented as the holy grail of accelerated development as the era of neoliberalism took shape.

In healthcare, the document and its supporters in Africa and amongst global capital called for the privatisation and commodification of healthcare delivery. So-called ‘user fees’ first appeared. While noting that this would be “unpopular” (most of the young states had committed to providing public health for all following decolonialisation) Berg and the World Bank argued that there was a scarcity of financial and institutional resources. Accordingly, user fees needed to be introduced not only in the urban areas but also for poor peasants in the countryside.

The report explicitly called for rural health workers to “establish themselves in in the villages and provide services for fees”. Condemning the publicly provided drugs schemes established in most African countries the document signalled a shift towards a market-oriented pharmaceutical policy, turning to ‘Big Pharma’ and, increasingly over time, US-based health charities like the Bill and Melinda Gates Health Foundation to provide essential drug treatments. It further called for a relaxation of the public sector’s role in the training, certification and supervision of paraprofessionals in health and sanitation, a move towards lowering the monitoring of public health standards.

Following this ‘turn to the market’ the debt burden of African countries exploded. With little choice but to seek help from the International Monetary Fund, there followed the on-set of aid-with-conditionalities and structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) regimes that still pervade. The neoliberal incarnation of capitalism took deep roots in the soil of the most underdeveloped continent on the globe. SAPs adverse impact on healthcare in Africa and across the developing world can hardly be overemphasized. Despite all fine words of governments and international organisations to the contrary, the lofty aim of public “health for all by the year 2000” adopted at the historic Alma Ata conference of the World Health Organisation and UNICEF in 1978 was thrown out of the window.

The unholy trinity of SAPs – privatisation, deregulation and liberalisation – exacerbated the ill effects of the deteriorating social and economic determinants of health. Unemployment rates, poverty and social inequality all spiralled. Government officials urged working-class people to tighten their belts for just a little while, while they continued to feed off the fat of the land. The bosses in government and their cronies bought up privatised state-owned enterprises and benefited immensely from contract rackets opened up by the SAPs.

More specifically, global capital directly attacked health systems with SAPs. In 1987, the World Bank’s Financing Health Services in Developing Countries explicitly laid the blueprint for privatisation of health services. Its guidelines included generalisation of user fees in public health facilities, the introduction of private insurance, encouraging provision of health services by NGOs and the decentralisation of public health systems. Here lie the roots of the Public Private Partnerships, governments as ‘purchasers not providers’ of health provision and so on, so familiar across the globe in developed and under-developed countries alike.

Emboldened in an era of capitalist triumphalism, in 1993 the World Bank went further with the publication of Investing in Health. This introduced the disability adjusted life year (DALY) model, developed for the bank by Harvard university, as a way of calculating overall average disease or disability burdens in specific populations. Health was thus effectively reduced to a measurable metric in order to estimate potential costs. Health became focussed on the ‘cost effectiveness’ of governments’ health investments, with investments guided by the principal of ‘best returns’. In this scenario, for the capitalist low-value labour such as disabled or chronically sick people represent poor investments. Tragically, we are beginning to see some of the consequences of this approach during the pandemic, with stories beginning to surface of ‘scarce’ testing, ventilators and other life-saving equipment being rationed for older people and those with underlying conditions.

The ‘scarcity’ argument is, and throughout, has been faulty. It is not that resources are not available; it is that the money to pay for them is diverted into the private profit of big capital. Global and local capital collectively continue to milk Africa dry. Capital flight from 30 Countries in Africa between 1970 and 2015 amounts to $1.4tn. With lost interest, this adds up to $1.8tn. In 2015, the Mbeki panel set up by the African Union established that $50m was lost annually through illicit financial flows. By 2018 this had risen to $80m! Yet, while sub-Saharan African countries spent 3.8% of its GDP to service debt in 2000, it used a mere 2.8% on health! Meanwhile, studies show that neoliberal policies of the IMF and African Development Bank between 1990 and 2005 led to the exacerbation of maternal mortality, resulting in at least 360 additional maternal deaths per 100,000 births.

Radical nationalists might point out these gruesome facts show the continued imperialist domination of the continent and leave it at that. But imperialism is not something disembodied from capitalism, an international system which binds together the bosses of all lands in uneasy alliance, including the richest bosses in Africa itself. For example, the three richest Africans own more wealth than the 650 million people constituting the poorest 50% of the population, a staggering figure.

Without a sense of irony, the African Union gathered governments and “business leaders” together in 2019 urging private capital to invest (for a profit!) in health because, as they said, ‘more than half of Africa’s population currently lack access to essential health services, and millions die every year from commonly preventable diseases.” This, then is the historical and current political context within which the pandemic has spread to Africa. This is the socially determined context of health that warns us of the potentially disastrous impact of Covid-19.

A public health and social-economic explosion in slow motion

At the beginning of March, the French 24 media said: “whether it’s a matter of faulty detection, climatic factors or simple fluke, the remarkably low rate of coronavirus infection in African countries, with their fragile health systems, continues to puzzle – and worry – experts.” Obviously, low testing capacity is a problem and the actual case and fatality figures are likely to be much more than the confirmed figures. Up till the second half of February, “only two African countries — Senegal and South Africa — had laboratories capable of testing and confirming samples for the virus.”

Now, there are testing centres in 40 countries. But the number of persons tested daily remains mainly in the hundreds, utterly inadequate in a continent with 1.3 billion people. Governments, in virtually every country on the continent as in other regions, have closed schools and many a public space. Major cities and states like Lagos and the Federal Capital Territory in Nigeria were put on lockdown. Most other states followed suit. A curfew was imposed across Kenya as it moves further towards complete lockdown. The most comprehensive national lockdown on the continent and “one of the strictest lockdowns introduced anywhere in the world” has been in South Africa. This step declared by the government on 26 March was initially for 15 days but has been extended to the end of April.

But these measures have been exceedingly difficult if not downright impossible to follow for the millions of poor working-class people across the continent who live on what they can earn from on a daily basis. Self-isolation and ‘social distancing’ amount to nothing but a mirage for many of these who live in slums and overcrowded apartments. Not surprisingly, there are pockets of resistance. The state meets these with force. Within the first three days of the lockdown in South Africa, not less than six people were killed by the police compared to five deaths at that time from Covid-19 infection. Similarly in Nigeria, eleven infected persons had died by mid-April, eighteen had been killed by the police effecting lockdown.

There have been widely reported cases of police assault against poor people in Kenya, Benin and Zimbabwe where almost 2,000 people were arrested in the first week of lockdown. Even health workers have been intimidated while attempting to provide needed services after the curfew in Kenya. And four people had been killed as well, less than the number killed by the disease at the time. In Uganda, where the government’s “$75 million supplementary budget request to help fight the coronavirus outbreak had more funds for security than health”, a 23-year old “was tortured in her neighbourhood by members of a paramilitary group”. And the Rwandese police also killed two people for defying the lockdown.

These “ruthless” authoritarian measures have been celebrated, including by the BBC, as being necessary to battle the pandemic. The South African minister of health has acknowledged that “a heavy and devasting storm” of infection may be on the horizon. But no matter how justified this makes lockdown crackdowns, they are not sufficient to contain the series of social and political storms unfolding. To divert popular attention from the coming storm, the South African government is also playing the xenophobic card. According to Al Jazeera the government declared its intention to “build a 40km (25 miles) fence along its border with Zimbabwe to prevent undocumented migrants from entering and spreading coronavirus”. This was at a time that the neighbouring country had no confirmed case, while there were already 150 confirmed cases in South Africa.

The severe shortage of healthcare workers across the continent cannot be addressed overnight. While countries have been building isolation centres in preparation for spikes in cases, the few healthcare workers at hand have very limited provision of personal protective equipment (PPE). Many have had to buy simple surgical masks which have increased in price by upwards of 1,000% in the market. This and other issues have led to strikes of doctors and nurses in Zimbabwe. Their demands, like those of nurses in Liberia during the 2014 Ebola outbreak, is for provision of PPE to safeguard their occupational health.

Currently, whilst health workers account for only 0.55% of the global population, they constitute 12% of the people infected by the virus worldwide. The situation will worsen with the likelihood of a surge of contagion in Africa. Low-paid community health workers are even more exposed by the shortage of PPE. They are explicitly denied PPE to make what little there is available for healthcare workers in hospitals. Meanwhile, community health workers are at the forefront of contact tracing, leaving them both extremely vulnerable and potentially key infection vectors.

Several governments have made announcements of palliatives to ameliorate the conditions of working-class people. But where this have materialised at all, they have been laughable. For example as Femi Aborisade reports on RoAPE, 650 people on a street were given a 45pence loaf of bread to share. It is becoming more obvious by the day that workers are in for a rough ride. In South Africa, the government has tried to cajole public sector workers into accepting salary cuts for a Covid-19 solidarity fund. Municipal workers have rejected this. In Nigeria on one hand aviation companies have sent WhatsApp messages to staff saying that they will not be paid for the time they are on furlough, whilst on the other, the construction company of Aliko Dangote, owned by the richest man in Africa, continues to work with the support of the government despite not providing any essential service.

With about 80% of working-class people in the informal economy, the lockdown aimed at saving lives will equally be ruining hundreds of millions of people’s livelihoods. Propositions for waivers of house rents and utility bills as well as genuine and palpable palliatives have been made by unions and civil society organisations in different countries on the continent. Governments have thus far ignored them. Governments seem more fearful of how bad the economic crisis, already beginning to express itself even before the onslaught of the pandemic, will be.

The estimation of 3.2% GDP growth for 2020 has already been almost halved, down to 1.8% with the likelihood of this falling further. The United Nations has projected a sharp recession. The World Bank estimates that between $40bn and $79bn in hitherto estimated revenue could be lost as a result of the outbreak, while the Africa Union which has put the launch of an African Continental Free Trade Agreement in July on hold, has warned that up to 20 million jobs could be lost.

Conclusion: the imperative of struggle

There have been responses to the unfolding public health and social-economic explosion by different social forces. These include two separate calls by groups of intellectuals mid-April. The first issued as an open call by 54 persons including a former president of Liberia condemns reactivation of “Afro-pessimism” due to the vulnerability of Africa due to “catastrophic effect of decades of structural adjustment on public health and health provision in African countries”. It further calls on Africans to have confidence in themselves and “support the global precariat” created by the pandemic! The second by 88 persons is a letter to African leaders “of all walks of life”, saying “the time to act is now”. It equally speaks to “chronic precarity” on the continent and condemns “chronic under-investment in public health” calling on governments to “govern with compassion”. And it takes a more explicit stand for Pan-Africanism with “a renewed lease of life” as the basis for its envisaged “radical change of direction” on the continent.

While such calls reflect the urgency of the situation, they should be recognised by working-class activists for what they are. These are efforts of the “well-to-do middle classes” to confront the crises in a way that mediates revolutionary pressures from below with reforms that fail to address, indeed divert attention from, the class basis of ostentatious wealth for a few and pauperisation of the immense majority of the population. The pandemic can be addressed, and fundamental change won only through revolutionary struggle of working-class people and radicalised youth.

Countries which witnessed democratic revolutions on the continent last year present sharp examples of response to COVID-19 from below. In Algeria, the Hirak Movement of the revolution “is taking charge of the health crisis”. And “once again, civil society is offering the answers, not the state.” Realising the potential this holds for another revolution, the government is also trying to exploit the outbreak to crackdown on the revolutionary movement. A similar trend can be seen in Sudan where Resistance Committees which established during the revolution had become key players in local neighbourhoods as an alternate power from below, the government hopes to arrest the simmering revolutionary spirit as it announced a lockdown to fight the pandemic, mid-April.

Now more than ever, working-class people, radical and revolutionary groups across the continent need to unite and fight. Only working-class struggle can change the systemic basis for the public health, social and economic crises. The class’ fight must be based on fundamental demands which address key issues of the moment as well as the underlying structural issues of social inequality and the prioritization of profit over life. Despite the limitations brought about by the lockdown, united fronts and with such programmatic perspective are emerging from the covid furnace.

The most significant of these is the C19 Peoples Coalition in South Africa. Its 10-point programme of action calls for: income security for all; housing and access to sanitation and clean water for all; universal access to food and nutrition; community self-organisation, local action and national coordination of the response movement from below; protection of community health workers and all other frontline and emergency services workers; strategies for calming tensions and nipping domestic violence in the bud; free, open and democratized means of communication; addressing digital and other forms of inequalities in educational services delivery in an era of remote learning, and; preventing nationalist, authoritarian and security-focussed approach in containing the virus.

This wide-ranging set of demands, highlighting the deep inequalities at the root of the effects of this pandemic, has inspired similar efforts in Nigeria, albeit on a more limited scale. Centrally, the C19 Peoples Coalition example is that the crisis it attempts to address is an existential one for working-class people globally. The bosses will want to make us bear the burden of recovery in the aftermath of the pandemic. Our response, now, must encompass both tactics for addressing the immediate and crucial questions, and a strategy for revolutionary transformation of society.

Our class cannot afford to fail. The alternative would be catastrophic, and this is already starring us in the face. In Nigeria for example, there was a wave of brazen robberies by lumpen youth, known as “area boys”, in its major city and neighbouring states in the second week of April. Hungry and angry after weeks of being shut out of their “hustle” on the streets, they threw all caution to the wind. The rise of such elements could become generalised, and a feeder for fascistic politics of populist capitalist politicians. Spontaneously youths in communities organised self-defence committees.

Socialists need to argue for self-defence committees wherever they emerge, to understand the linkages between the flotsam and jetsam of “area boys” and the capitalist system. We also have to argue within our unions across the continent, and particularly so to the rank and file as the bureaucracy have been rather reticent in taking action, for decisively bring workers power to bear on the brewing popular anger below the pandemic’s surface.

The period we are entering is pregnant. Contradictions are deepening and in different ways, several social forces are mobilising to define the way forward in the crisis. We, as workers, must not lose sight of the fact that, at the heart of the global emergency is the crisis of capitalism. Without winning the overthrow of this anti-working people system, we are bound to sink into deeper mire of barbarism in an age of pandemics and climatic disaster which affects us all.

by Baba AYE

April 2020