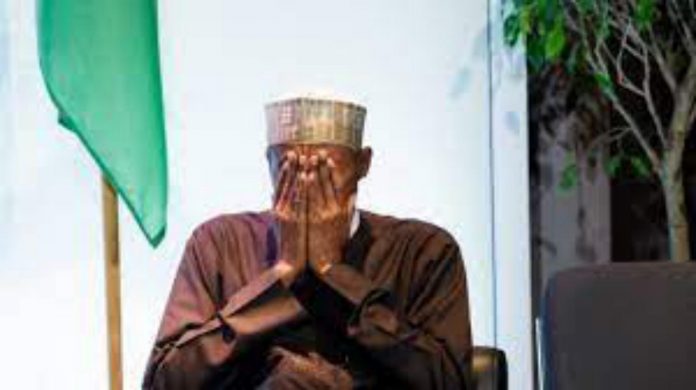

In 2015, General Muhammadu Buhari swept to power on the promise of being a much-needed messiah. With his decades of military experience, we were told, he would root out the insecurity that has steadily engulfed this country. His self-declared integrity and imperviousness to corruption were supposed to be the weapon with which he would fight corruption until defeat. His assumed loyalty to the poor and rural, particularly to the rural populations in the north, was supposed to mark a clean break from the neoliberalism of past regimes. Eight years have come and gone, and the scorecard is an F on almost all fronts.

Starting with education, it is instructive to point out that Major Gen Buhari inherited an education sector already incapacitated by underfunding and insecurity. But rather than improving the situation, he left it worse. At the time he came into office, Nigeria suffered periodic university closures due to strikes and had 13.2 million out-of-school children, the largest demographic affected being girls in the North. Today, that number is 20 million. Funding for the education sector did not only fail to rise to the recommended percentage of GDP, but also failed to even keep up with inflation. The Academic Staff Union of Universities broke its record for the longest strike held under Buhari’s watch. And insecurity caused school closures across the country. Despite the welfarist reputation he somehow acquired before becoming a civilian president, it was also under this administration that the government shifted concretely towards full privatisation of the tertiary education sector. Even the recent student loan bill that President Tinubu assented to was introduced to the National Assembly, while Buhari was still president and national leader of the All Progressives Congress (APC).

His tenure has also seen cuts to funding for healthcare, most shockingly in 2020 when healthcare spending was slashed by 40% in the middle of a global pandemic.

In the area of civil rights and liberties, Nigeria has regressed even further. From state sanctioned sexism to the attempt to ban gender non-conforming dressing to the subjugation of and violence against ethnic minority communities to police violence and impunity from all arms of state security. In 2020, the Nigerian people revolted in what is widely known as the EndSARS protests and were met with brutal repression from the Buhari regime.

Going on to Agriculture, we saw more direct state investment from the Buhari administration, with millions of farmers accessing credit which showed some gains, albeit minimal, particularly in rice production. But this was again implemented under a framework of neoliberal conditions. Most of Nigeria’s farmers are subsistence farmers and there were no efforts to collective agriculture or to create incentives for cooperative farming. Within this context, the credit facilities led to little mechanisation.

All the platitudes about eating what we grow and growing what we eat, all the promises of food self-sufficiency ended in clear failure. Under his government, the agriculture sector’s growth was at its weakest since 1999.

Insecurity has blown from the North-East and the North-West to every part of the country. We now have generalised insecurity affecting every part of the country with banditry, kidnappings, terror against ethnic minorities in the North, and IPOB-imposed curfews in the South-East over the continued illegal detention of Igbo secessionist leader, Nnamdi Kanu. There is hardly a day now when a new terror attack is not reported. All the promises of what his experience as a Major-General could bring to bear have turned out to be emptier than dry wells.

His track record on Infrastructure is not much better to write about. Granted that the administration did more on infrastructure investment than any other administration since the return to democracy, racking up perhaps worrying levels of debt in the process, but much of it was repairs or completion of inherited infrastructure projects. Most of Nigeria’s 200 thousand kilometres of roads remain unpaved and we have less than 4000km of rail. By comparison, South Africa, which has a smaller population and landmass, has about 21,000km of rail. And rail infrastructure is where the regime gets its highest marks from its supporters. After 3 decades, the 327km Itakpe-Warri Standard Gauge Rail was finally completed and opened in 2020. The 156km Lagos-Ibadan Standard Gauge Rail was completed in four years. The 186km Abuja-Kaduna Standard Gauge Rail Line was also completed. But this still leaves most of the country unconnected by rail, and insecurity continues to plague our rail lines. The Buhari regime also spent a whole lot on the power sector, investing trillions of naira across the sector only for the masses to reap higher electricity tariffs and unstable power supply.

But one of its worst records is its utter contempt for labour rights, demonstrated by its aggression towards unions, clashing with all major unions in eight years. Healthcare workers went on strike several times. Industrial workers went on strike repeatedly. Education workers went on strike without ceasing. Transport workers went on strike as well. Civil servants went on strike on a number of occasions. And the Buhari regime fought tooth and nail each time, instead of conceding to the workers’ demands. There were times when it was forced into compromise, most prominently its increase of the minimum wage from N18,000 to N30,000, as against the unions’ demand for N52,500, after a series of general strikes in 2018. But in general, this regime had a consistent policy of antagonism towards organised labour. We, unfortunately, saw the weakening of so many important labour unions, with ASUU being forced to end its strike by court order and a rival academic staff union, Congress of Nigerian University Academics (CONUA) granted registration by the Federal Ministry of Labour and Employment in 2022. This weakening is one of the ways the Buhari regime paved the way for the neoliberalism of the Tinubu administration. The worker formations that have resisted things like subsidy removal and university privatisation are the weakest they have ever been. In that way, this administration has been a banging success for the Nigerian ruling class, even if it has left them as divided as they have ever been. And for the working masses hunger, abject poverty and destitution. Nigeria now has more people living in poverty than any other country in the world. Insecurity has engulfed almost every part of the country and there is an aggressively neoliberal new APC government.

Any objective analysis of the 2015 – 2023 Buhari regime will find that it failed on all metrics that concern nation-building, social welfare, security, and infrastructural development. And it got really high marks for ensuring the hegemony of imperialism and the r local ruling class collaborators. Perhaps it is yet even more important to understand that this is the inevitable consequence of ruling class rule in a time of crisis. Only socialism can light a humane path forward, towards social progress.

by Kayode Somtochukwu ANI