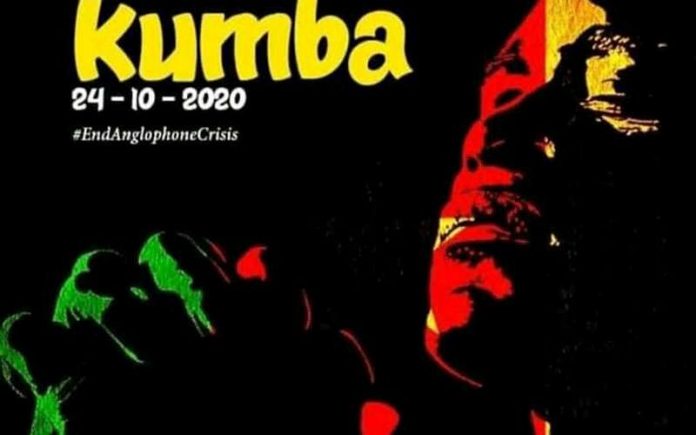

The world expressed shock at the news of the murder of eight pupils of Mother Francisca Bilingual International Academy, in Kumba a town in the English-speaking South West region of Cameroon, on 24 October 2020. At least twelve other pupils were also wounded by the plainclothes killers who drove in on motorcycles to attack the harmless children with guns and machetes.

This gory incident is yet another saddening act in the fratricidal civil war that has engulfed the country since 2017 which some analysts describe as the Ambazonia war. This war, which is part of what is also called the “Anglophone Crisis” emerges from what is commonly referred to as the “Anglophone Problem” in Cameroon. It is a legacy of global imperialist rivalry and the country’s peculiar colonialization where Germany, Britain and France took turns to pillage the land.

Cameroon was first colonised by Germany in 1884. This was formalised at the Berlin conference of 1884/85 where European powers sat down together to partition Africa in furtherance of their conflictual but at the same time common (i.e., in opposition to the peoples of the lands they were to exploit) imperialist interests. The colonialists established large scale farms on the fertile soil they found. Trading companies followed, to purchase agricultural products and expand the market for German goods.

Things changed for Germany with World War I. The allied forces, including Britain, France and Belgium launched a campaign against the Germans in Cameroon from 1914 to 1916. The British and French reached an agreement to divide the country as spoils of war, without regards to the configuration of the peoples and nationalities. Britain got one fifth of the lands (87,900 sq. metres as against 430,000 sq. metres for the French), covering two regions. These were the areas close to its Nigerian colony.

The League of Nations merely formalised this arrangement with its mandate after the war. The Versailles Treaty as law only “blessed” what had been seized with force. Thus, were the landmines of today’s conflict laid. The United Nations which was born after World War II did not do anything different from the League of Nations despite describing “mandate territories” as “UN trust territories” which supposedly were to be run by colonialists in the interests of the indigenous populations.

Britain ruled its own portion of the territory from Lagos, the capital of its Nigerian colony. France on the other hand, was more in control with the larger territory and what was the capital of the colony. When the Union des populations du Cameroon emerged as a nationalist movement in 1948, it was viciously repressed. Hundreds of its militants were killed. It then turned to armed struggle, led by Ruben Um Nyobe, a communist and trade unionist. Nyobe was brutally murdered by the French army on 13 September 1958 and the mere mention of his name made illegal until flag independence was granted. His successor, Felix-Roland Moumie was also assassinated, this time by the French secret police in Geneva.

Nigeria and Cameroon both gained flag independence in 1960. A referendum was organised in 1961 to determine which of the two countries the English-speaking (because they had been colonised by Britain) territories would be a part of. The northern region voted to stay with Nigeria becoming the Sardauna province of Northern Nigeria, which is spread across parts of today’s Adamawa, Borno & Taraba states. The southern region voted for re-unification with Cameroon. But while it was thus re-unified, from the very start, its peoples were never fully integrated into the country’s decision-making processes. This was partly because France continued to dominate the country. Jean-Pierre Bernard, the French ambassador at the time was often described as the “true president” of Cameroon.

After years of a one-party system, there was a turn to multipartyism in the 1990s. And in 1996, a new constitution was enacted which promised decentralisation. But this did not come to be. Instead, French-speaking magistrates and teachers were deployed to the English-speaking regions. This deepened Anglophone Cameroonians’ sense of marginalisation.

As this situation persisted into the second decade of the 2000s, lawyers embarked on strike in 2016. The government’s response was brutal. They were beaten up. Teachers in the Anglophone regions also went on strike in October 2016 to demand an end to enforcing French as language of instruction in schools, and in solidarity with the lawyers. The strike lasted three months, with all schools in the two regions shutdown. But government did not budge. There were mass demonstrations in support of the strike’s demands in the communities. More than a hundred persons were arrested and at least six shot dead.

During the strike, Anglophone Archbishops also echoed the regions’ grievances in a letter to Paul Biya the country’s president. They pointed out that the Cameroonian state had never respected the constitutional provision to protect the identity of Anglophone Cameroonians. The change of the country from a federation to unitary system in 1972 had contributed to this situation. The Archbishops argued that the referendum which led to this was handled in a questionable manner.

With this escalation of events, the “Anglophone problem” snowballed into an intense crisis and eventually the beginning of a low intensity civil war in 2017. Workers in the plantations went on a series of strikes. Women came out to decry the murders of hundreds of protesters in what some have described as a genocide. And eventually as all these failed, several separatist groups emerged, demanding the secession of Anglophone Cameroon to form a new country; Ambazonia.

These include the petite bourgeois Southern Cameroons Ambazonia Consortium United Front which declared a Federal Republic of Ambazonia in October 2017. The Consortium later reconstituted itself as an Interim Government of Ambazonia in exile (which has been ridden with internal crisis). The Ambazonia Governing Council (AGovC) which was established earlier in 2013 with the merger of a number of pro-independence bodies at the time, is also one of the leading players in the Ambazonian separatist movement.

The movement also includes over twenty armed groups such as the Ambazonia Defence Forces (linked to the AGovC), which launched a guerrilla war for Independence in September 2017. Some others are Ambaland Forces, Ambazonia Restoration Army, Gorilla Fighters, Red Dragons, Southern Cameroons Defence Forces, Tigers of Ambazonia, Vipers, and White Tigers. They generally have between dozens and hundreds of soldiers at the most.

While the armed groups memberships might not small, they have been able to enforce a ban on schools in the two regions. About 500 primary and secondary schools which make up 80% of these institutions in English-speaking Cameroon have been closed for the past three years. Pupils and their parents have been scared for the lives of these young people and their teachers.

The impact on children of schooling age cannot be overemphasized. In September, civil society activists in the region called for the schools to be reopened. This call was echoed by the Teachers Association of Cameroon. About 300 teachers responded to the call. Some of these were abducted by separatists in the first week of October. The government’s attempt to militarise the reopening of schools with soldiers bringing in teachers to school was however rejected in the second week of October. Nonetheless, by 21 October, the army began forcing pupils to attend school and teachers to teach.

The school massacre took place three days later. The government was quick to blame separatists, claiming a few days later that it had killed the leader of the guerrilla group which launched the attack. Several armed separatist groups have likewise denied culpability with the argument of it being stage-managed by government to give a dog a bad name for hanging it.

It is not clear to tell which side is telling the truth. But there are a few things that we, as working-class activists, must make clear.

First, children must not be made targets by warring parties. This is totally unacceptable. Second, the “Anglophone crisis” need not have been allowed to degenerate to this extent. We stand for the right of all nationalities to self-determination, up to and including the right of secession. The Cameroonian government must hold a plebiscite in the region to determine the democratic choice of the peoples of the two regions on remaining in the Republic of Cameroon or to stand as Ambazonia. And the result of such referendum must be respected.

If there is a majority vote for staying in Cameroon, the central government has to put federative measures in place which guarantee the flourishing of the different languages (and not only English or French) and cultures in the country along with improved social and economic wellbeing of all persons.

Third, the primary lines of division in society are those between poor working-class people who constitute the majority of the populace and the rich, parasitic few who wield political power. The oppression of poor people in Anglophone Cameroon is by a handful of rich people who also exploit and oppress poor working people in the majority Francophone parts of the country. Almost half of Cameroonians, across all language and regional divide live in abject poverty.

With the country’s weak production base, primitive accumulation in perpetuity through government is the main means of exploitation. Economic and political power have been concentrated in the hands of a few people who run the country. President Paul Biya personifies this.

He has been in the corridors of power since 1968, serving first as Secretary-General of the presidency under the Ahmadou Ahidjo the country’s first president, till 1975 when he became prime minister. And when Ahidjo stepped down in 1982 Biya stepped into the saddle as president, a post he has held on to till date with the support of France. This makes him the longest serving African head of state. And in this period, whilst the country wallows in poverty, he has raked in a personal wealth of up to $200m.

Be it in a united and bi-lingual or solely French-speaking Cameroon, working-class people must redouble their efforts to kick out the likes of Paul Biya and what they represent. They must fight for a working people’s government that runs society for the benefit of the immense majority of the population. The African and international working-class movement must boldly put the bloody national question in Cameroon on the front burner of public opinion.

Three thousand people have been killed in this crisis and half a million displaced from their homes. This must stop. We must demand an end to the crisis wrought by colonialism and being perpetuated by comprador capitalists running the neo-colonial country by playing up Anglophone and Francophone divisions. We must demand a democratic resolution of this crisis, with due respect for the right of all nationalities to self-determination within or outside the republic of Cameroon.

by Baba AYE