For the first time in four decades, Nigerian workers will mark May Day without parades and fanfare. Most of us will be at home, under lockdown like one third of the global population. Those at work would be medical and health workers battling the SARS-Cov-2 to keep us alive, and a few other workers in sectors delivering essential services necessary to keep society running. This must be a moment of reflection for us, on the significance of May Day, the pandemic, and its aftermath.

This will be the 130th commemoration of the international day of workers solidarity. Inspiration for a global day to demonstrate international workers solidarity came from the struggle of American workers to win the 8-hour workday. The Federation of Organized Trades and Labour Unions passed a resolution in October 1884 that all employers must respect the right of workers to 8 hours of work, 8 hours of recreation and 8 hours of sleep.

The ultimatum for the 8-hour workday to be accepted by employers was 1st of May 1886. Government and private employers were obstinate. And on that day, 300,000 workers across America commenced a general strike. In the middle of this strike, 3 workers were killed on 3rd May when trying to stop strike-breakers in front of a factory.

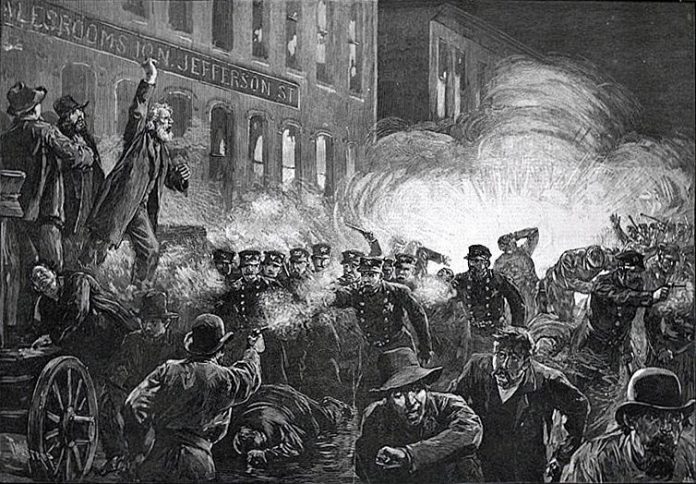

A peaceful rally was organised by trade union leaders at Haymarket square the following day, to protest this. The police moved in to disperse the rally and a bomb went off. This was a cue for the police, they fired into the crowd, killing four persons. The eight union leaders (including one that was not even at the rally), who were well known anarcho-socialists were arrested and tried for the bomb blast. Despite how ridiculous this was, they were found guilty by an obviously prejudiced judge. Seven of them were sentenced to death and the eight, to fifteen years imprisonment.

This dastardly act did not deter workers’ struggle for the 8-hour workday. Rather, a luta continued. And in 1888, the American Federation of Labour (AFL) resolved to organise yet another general strike, starting from 1st May 1890 if government and employers did not comply. It was the international socialist movement that turned this struggle in America to a worldwide fight.

In July 1889, radical activists gathered in Paris to establish an international federation of socialist parties, better known as the Second International. AFL sent a letter to this meeting asking for international support for the looming fight of the American workers. The Founding Congress of the Second International subsequently passed a resolution for workers of all lands to organise “a great international demonstration” on 1st May 1890. Ever since then, the day has signified International Workers Solidarity.

It was however not until 1980 that it became officially recognised by any government in Nigeria. First the Peoples Redemption Party governments in Kaduna and Kano made it a public holiday in the two states. The following year, the National Party of Nigeria declared it a national holiday.

There are a few lessons to learn from this brief history of the May Day. Probably the most important is that “freedom cometh by struggle”. The first International Labour Convention adopted at the founding of the International Labour Organisation in 1919 was on “working time”. Thirty-three years after the spark of the struggle for the eight-hour day was lit, it became the universal standard.

The establishment of the ILO itself was a strategic response of governments and employers to curb seething anger of the working-classes. The curtains had come down on the gruesome drama of the First World War. But several significant notes blended with the macabre symphony of war. Workers had overthrown an emperor in Russia and were taking tentative steps at building an envisaged new society. And the Spanish Flu, a grimmer reaper than war had been, stalked the land, in the second of its three waves of death.

That great plague claimed between 50 and 100 million lives worldwide. These numbers included 500,000 people in Nigeria, out of what was a population of 18 million people at the time. The greatest pandemic the world has faced since that dark moment is now on us in the lethal shape of Covid-19.

Unlike a century back there was no backdrop of a shooting war to the pandemic. But there was war quite alright. It was the war waged without mercy by the 1%, the super-rich billionaires against working-class people comprising the immense majority of the population. This war has taken several shapes over the last four decades as a neoliberal campaign; structural adjustment programmes (SAPs), privatisation, outsourcing, casualisation of labour, deregulation and so on and so forth.

Fourteen years ago, Warren Buffet, one of the richest men in the world put it clearly when he said: “There’s class warfare, all right, but it’s my class, the rich class, that’s making war, and we’re winning.” Just a few years after that, that rich class’ neoliberal project was revealed as the false god it is. Many proclaimed the death of neoliberalism, and even capitalism which it is an incarnation of, at the onset of the Global Recession in 2007/8.

But the super-rich came out stronger. They were able to get away with proffering more of the concoction (of privatisation, cuts in public funding, etc) which led to economic crisis as the only remedy for its ailment – until the Covid-19 global emergency. And this was possible precisely because of the limitations of the demands of organised labour in Nigeria and globally, twelve years ago.

This did not deter the rank and file of working-class people from rising. There were “massquakes” from below, which in several instances pushed the trade union bureaucracy into action and in others led to the emergence of new, radical-reformist parties. These took the form of resistance which boiled into revolts, like the January 2012 mass awakening in the country. Revolts, particularly in North Africa sparked revolutions. – Tunisia, Egypt and more recently; Sudan and Algeria

The pandemic puts the era of crises and revolts we have been living through in even sharper relief. The most successful efforts at curbing the spread of the disease have invoked what could be considered as nuggets of “invading socialism”.

Private hospitals have been nationalised or requisitioned to provide adequate Intensive Care Unit beds in Spain. Local factories have been taken over and converted to manufacture personal protective equipment and other needed medical equipment and supplies such as ventilators and disinfectants in Italy. Workers have been paid significant percentages of their salaries whilst asked to stay home under lockdown in several countries.

But this is not to suggest that the rich have conceded to a moratorium of the class struggle. The trade unions must not forget that eternal vigilance remains the price of liberty. Organised labour needs to seize this May Day to make it clear that there will be no going back to the normal of neoliberalism.

This “normal” was at the heart of the problem. It was why there were not enough PPE for health workers or even enough health workers to start with. It is why our public health system is in shambles. It is why Nigeria became the poverty capital of the world while the wealth of the five richest Nigerians could wipe out poverty in the country.

The demands of the time go beyond those of genteel dynamics of collective bargaining. Audacity, audacity and yet audacity is required of the working class. We must put forward radical demands based on workers’ power, for a developmental paradigm which puts people before profit. The struggle for what Nigeria and indeed the world will be after the pandemic starts now. For organised labour to have any historic significance, it must be realistic and demand the seemingly impossible – system change NOW!

by Baba AYE