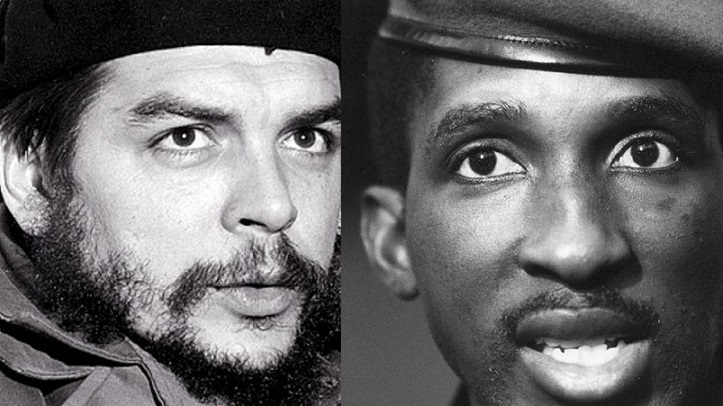

Che Guevera and Thomas Sankara were two revolutionaries that inspire youth and working-class people in the struggle for a better world. They were both murdered in the prime of their lives; Che on 9 October 1967, and Sankara on 15 October 1987. But as Sankara once said, “while revolutionaries as individuals may be murdered, you cannot kill ideas”.

Che was 39 years old when he was killed by a Bolivian soldier acting for American imperialism. Sankara, often described as “Africa’s Che Guevera” was 37, when his deputy Blaise Campaore treacherously murdered him and a dozen of his comrades. The two men were bold, charismatic figures inspired by Marxist ideas, who led anti-imperialist revolutions.

Born on 14 June 1928, Enersto “Che” Guevera grew up with an adventurous spirit and a strong aversion to injustice.

When he was twenty years old, he gained admission to study medicine at the University of Buenos Aires. Two years into his medical studies, he travelled around rural Argentina, on a bicycle. The following year he took a year sabbatical leave from school for traveling through South America on a motorcycle. The notes he took as he travelled were later published as the famous The Motorcycle Diaries.

In 1953, Che graduated from medical school and embarked on another journey through Latin America, ending up in Guatemala, where a radical government had been established led by President Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán. It enacted an Agrarian Reform Law in 1952; redistributing land to the benefit of poor landless peasants. United Fruit a US multinational company was the largest landowner in the country and was made to forfeit 225,000 acres of land.

Ernesto Guevara felt at home in this revolutionary moment. This was where he got the nickname Che, which in Latin America meant “my paddy”, the word he used to greet people. He established relations with activists in Arbenz’s party and members of the July 26 Movement led by Fidel Castro in exile.

But, imperialist America helped organise a counter-revolution against Arbenz’s government. The military took over power killing hundreds of activists, particularly communists. The trade unions were equally smashed and all lands seized from United Fruit returned.

It was during this period of counter-revolution, that Che became a Marxist. The triumph of reaction, initiated by and sustained by American imperialism also convinced Che that the road to revolutionary power would have to be through armed struggle.

Thomas Sankara was born on 21 December 1949. He had his elementary education in Bobo-Dioulasso, the second largest city in the French colony and proceeded to lycée Ouezzin Coulibaly for secondary education. After this, he joined the army.

Sankara came in touch with radical ideas at the military academy, through Adama Touré, the academic director. Shortly after, he proceeded to Madagascar for officer training, and witnessed uprisings against the country’s government. This was where he started studying the Marxist literature. He returned home in 1972 and became a well-known figure in Ouagadougou, the country’s capital, loved for his simplicity and as a guitarist.

In 1980, a coup d’état was staged by Colonel Saye Zerbo. A year later, Sankara was made Secretary of State for Information. He resigned seven months after, protesting the government’s repression of trade unions. He set up a secret Communist Officers’ Group with some radical colleagues in the army.

On 4 August 1983, the group organised a coup d’état which had popular support, marking the beginning of what Sankara described as a Democratic and Popular Revolution. He was assassinated four years later, on 15 October 1987, with twelve other comrades. But in the space of those years he took far-reaching steps to turn around the lives of working-class people for the better.

He carried out agrarian reforms, redistributing land to poor peasants. Feudal chiefs that were landlords were stripped of their exploitative power of forced labour. Food sufficiency was achieved. Healthcare and social services were prioritised. Mass immunisation programmes were organised, Large-scale housing schemes were completed and the danger of HIV and AIDS was acknowledged for the first time by an African leader.

Thomas Sankara had a pride of place for women’s rights. He insisted that “we do not talk of women’s emancipation as an act of charity or because of a surge of human compassion. It is a necessity for the triumph of the revolution.” Female genital mutilation, polygamy and forced marriages were banned, while contraception and female employment were promoted.

Sankara acknowledged the strong influence of Che Guevera -whom we now return to- on his politics when he said: “Che Guevara taught us we could dare to have confidence in ourselves; confidence in our abilities. He instilled in us the conviction that struggle is our only recourse.”

Che moved to Mexico in 1954, after the fall of the Arbenz government in Guatemala. He worked at both the Mexico Children’s Hospital and the city’s General Hospital. Meanwhile, he also re-established ties with Cuban revolutionaries he had earlier befriended. It was through these he was introduced to Raul Castro and Fidel Castro mid-1955. He joined the July 26 Movement and its Rebel Army that headed to Cuba on the Granma boat in November 1956 to wage a guerrilla war.

Che proved himself to be a passionate and gallant fighter. He also helped to build health clinics and school sessions to teach poor peasants how to read and write. On 1 January 1959 Batista abdicated power. The rebels took over the machinery of state.

Che played critical roles in formulating and implementing revolutionary reforms. He drafted the Agrarian Reform Law which, redistributed land, by limiting the size of farms that individuals could own. Cooperatives were also encouraged and state-run communes established on some expropriated lands. 1961 was dubbed “year of education” in Cuba. Volunteers went to rural communities in a massive literacy campaign. Literacy rate then was about 70% in the country. Today it is 99.7%.

In the first quarter of 1965, Che Guevera disappeared from public life. He wanted to spark or strengthen armed struggle for revolution in the Third World, starting from Congo, where he tried to work with what turned out to be an unruly band of guerrillas under the command of Laurent Kabila and ultimately to Bolivia where he tried to build a guerrilla army but was captured and killed on 9 October 1967, by Bolivian troops aided and guided by the American CIA Special Activities Division.

There are several lessons for us as working-class activists and as youth, to draw from the lives and politics of these two revolutionaries. These include understanding the shortcomings of the revolutions they led, without dampening the inspiration they provide.

Despite some efforts at establishing grassroots-based structures of power, their revolutions were largely from above. Power was seized through armed struggle on one hand and a coup d’état on the other hand; not through the independent self-conscious mobilisation of the working-class in both cases. Using the state, their programmes fostered socio-economic modernization. But, the soul of working-class power from below was stifled. The trade unions and freedom of the press largely suppressed.

It could be argued and not without some merit that they were revolutionaries who reflected their times and seized hold of the structures best available to them through their politicisation processes. But these should not make us lose sight of the centrality of workers’ struggle from below as agency for socialist transformation of society. The emancipation of working-class people can be won only as self-emancipation.

We must dare to struggle, and in doing this as Thomas Sankara advised “dare to invent the future”. This requires tenacity in building workers’ power and class consciousness, in anyway and every way we can, towards the international overthrow of the exploitative capitalist system, and the building of society anew, on pillars of solidarity, and democratisation of all facets of our social life.

Long live Che! Long live Sankara!

by Baba Aye